This article was originally authored by Tom Ogletree here.

Today’s workforce is not just changing. It’s undergoing a seismic shift that, according to the McKinsey Global Institute, “is happening ten times faster and at 300 times the scale, or roughly 3,000 times the impact” compared to the Industrial Revolution.

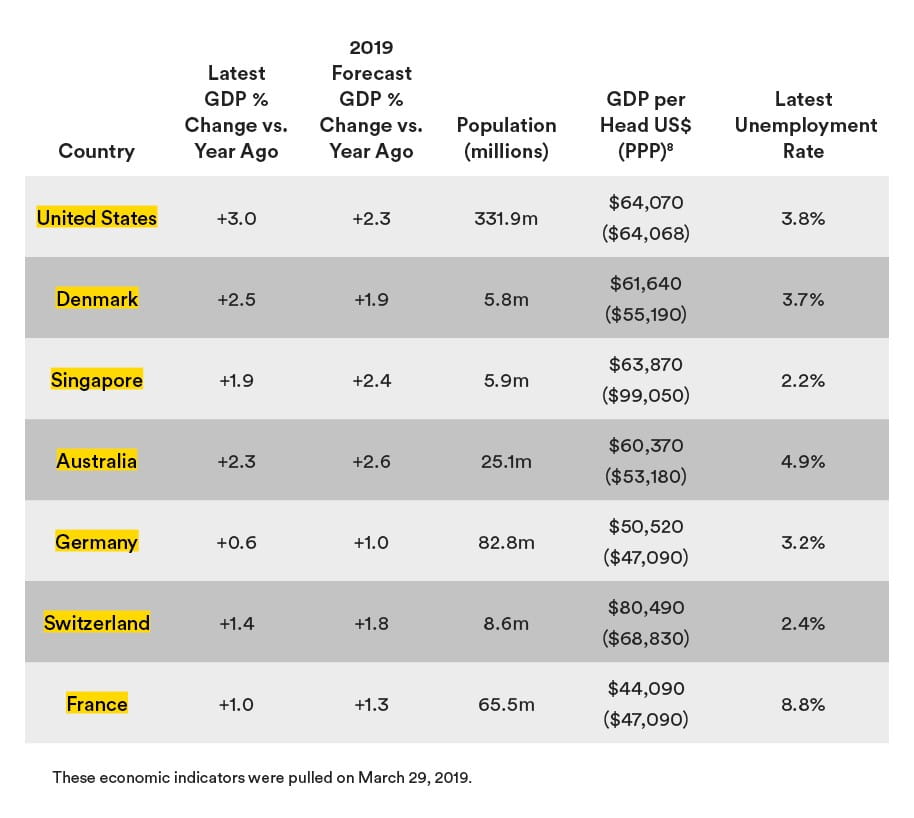

The reality is that professionals grapple with a volatile economy where the shelf-life of skills is shrinking, hybrid jobs are increasing, and fears about automation’s disruptive impact on the job market make headlines every week. In the U.S., despite surging stocks and historic GDP growth, people’s incomes and wages haven’t kept up and income inequality continues to accelerate.

Around the globe, governments and employers alike recognize that areas such as AI and automation are quickly reshaping the workplace. And the gap between the skills workers have and the skills companies need is growing wider as workers struggle to keep pace with emerging technologies in fast-growing industries.

In my role at General Assembly, I get the opportunity to speak with U.S. policymakers and analysts who grapple with employment and workforce development issues, and formulate solutions to ensure Americans can succeed in the new world of work. In these conversations, examples of education and workforce investment models spearheaded in other cities and countries often come up, and how we might repurpose them. Global training providers like GA are also partnering with organizations to craft upskilling and reskilling programs that arm professionals with cutting-edge skills, and also generate creative sources for talent in an increasingly competitive market.

We know technology is transforming the global workforce. What’s less clear is how this transformation will take place — and what policymakers, learning and development providers, and business leaders should be doing to prepare for it.

Navigating the Future of Work Through a Global Lens

In our new white paper, which we developed in collaboration with Whiteboard Advisors and features a foreword from former Acting U.S. Secretary of Labor Seth Harris, we uncover a lot of useful insights about how the U.S. and other industrialized nations are navigating these employment and workforce issues. Our study examines the experiences and policy initiatives of six countries — Australia, Denmark, France, Germany, Singapore, and Switzerland — and their strategies to improve upskilling, economic mobility, and employability in an evolving, and, at times, turbulent marketplace.

While the U.S. economy and labor market have unique characteristics, we discovered there are lessons to be learned from other developed economies pursuing workforce development programs and initiatives.

For example, we examine Australia’s Vocational Education and Training (VET) program, which provides government support toward helping people pursue non-college skills training. Or, consider Germany’s Dual Training System, where companies partner with publicly-funded vocational schools to provide job training.

As American politicians, educators, and business leaders, we must ask ourselves: How can the startling impact of these innovative approaches be applied within a U.S. context? It’s a question industry stakeholders and experts have posed to General Assembly with increased frequency since we were acquired by The Adecco Group in April 2018. As the largest human capital solutions company in the world, The Adecco Group is an active participant in the highly successful Swiss apprenticeship model, a government-led initiative that provides young Swiss professionals paid apprenticeships designed in partnership with Swiss companies, and that’s recognized around the world as a paradigm for work-based learning.

Putting the Future of Work in a Global Context offers a high-level analysis of these and other examples of skill- and employability-building initiatives in industrialized nations, as well as a few observations:

Nobody has it figured out.Even when there are highly sophisticated programs in place that combine the best of the public, private, and social sectors, these programs haven’t always had the desired impact. For example, France’s Personal Training Account (“Compte personnel de formation” or the CPF) enables private and public sector employees to track work hours, which turn into credits for vocational and professional training schemes. On paper, access to training dollars with no strings attached seems like a surefire way to ensure French citizens can consistently upskill and reskill. However, just 6% of French workers took advantage of the training, despite the reality that 64% of that population would like to retrain in a different field.

Exportability is great in theory but tough in practice. Most of these programs are inextricably linked to the highly specific dynamics among labor market actors — companies, unions, and education and training providers — within each country, making it hard to replicate the best ideas elsewhere. Denmark’s “Flexicurity” model has some incredibly compelling features. Workers have greater security through generous government-funded unemployment benefits and education, retraining, and job training opportunities that help them return quickly to the labor market after they lose a job. Employers also win thanks to flexible contracts that allow them to hire and fire at will without incurring excessive costs for dismissing employees. As a result, litigation due to dismissals is rare. It would be difficult to imagine this program functioning in a large, heterogeneous country like the United States, which lacks the same tight alignment between government, employers, and trade unions.

There are still many good ideas worth exploring further. That’s not to say there isn’t massive potential in these models, which can inform U.S. domestic education and workforce policy. Given the breadth and variety of American industry, it would be hard to imagine the level of coordination and cohesion, which has made the Vocational and Professional Education and Training System (VPET) such a success story in Switzerland, working stateside. With that said, many of the guiding principles — stackable credentials, designated learning pathways, and funded apprenticeships — could be replicated in the U.S. It’s already happening: the Swiss-American Chamber of Commerce, along with Accenture, delivered an in-depth report in 2017 that demonstrated how various Swiss companies have adapted the VET program, some for more than 10 years, for their U.S. operations.

Today’s increasingly global workplace demands a more nuanced, comprehensive understanding of the different ways governments and industries are addressing and responding to economic mega trends. Our hope is that this paper can begin a conversation about the lessons, ideas, and insights that other countries have to share with U.S. policymakers, employers, and practitioners on how to respond to and anticipate the future of work.

Download the Putting the Future of Work in a Global Context white paper.

Earlier this year, the Adecco Group announced its new global commitment to upskill and reskill five million people around the world by 2030. The Adecco Group plays an active role in ensuring that individuals can fulfill their potential in this changing world of work and that companies and institutions have access to the talent they need to capitalise on the future opportunities ahead of them.

Tom Ogletree, Senior Director of Social Impact and External Affairs at General Assembly

Tom leads GA’s public policy and communications, and oversees social impact programs that empower low-income adults from underrepresented communities to acquire digital skills and pursue tech careers.